Is there a better tomorrow?

Sometime ago, I learned there is a genre called grimdark where the books are unrelentingly grim and dark. Different people describe the genre differently. Some say, it is about books that are realistic, where no one is either good or bad, and all choices are messy. Some say, it is about a nihilistic view of the world where there is no hope, no right choices, and no redemption. (I do think nihilism is the equivalent of a shrug in moral philosophy — every choice is flawed, so why bother with debating the right one.)

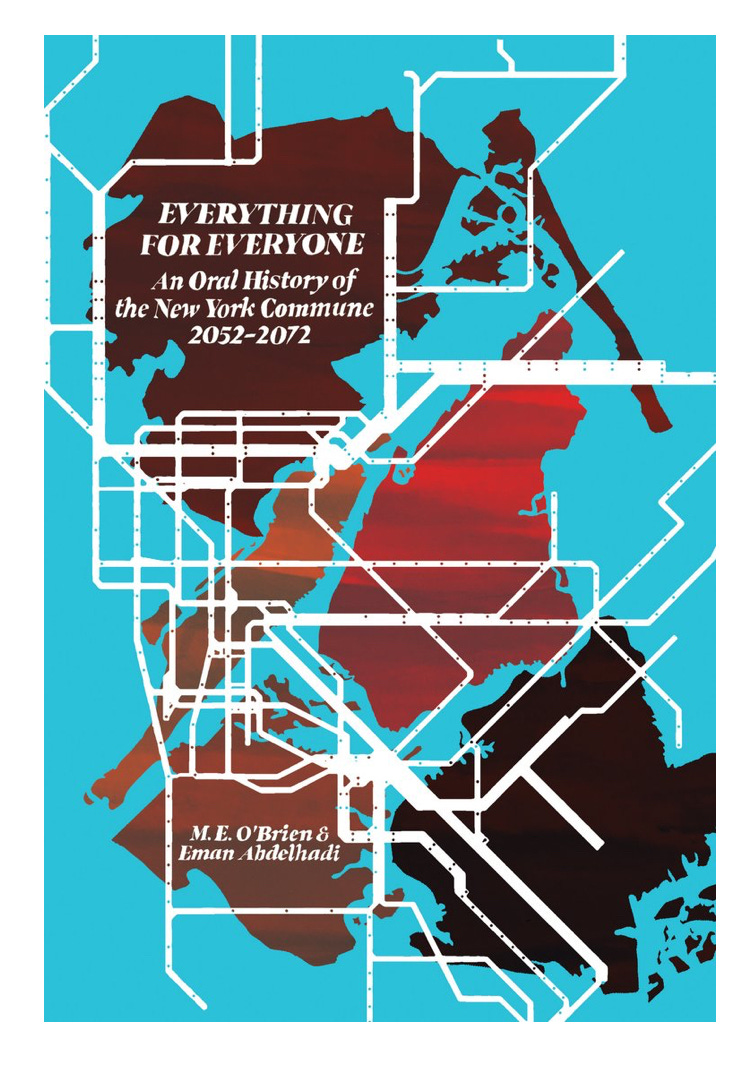

Given the situation today, a grimdark novel as an artistic response seems understandable. ‘It was the worst of times, it continued to be the worst of times’ is probably how novels imagining the future will begin and end. And yet. If art is to be our refuge, if imagination is to be the way we find ourselves out of this morass of the status quo, then, what does a hopeful imagination of the future look like? I don’t mean Bollywood escapism, a suspension of reality for a moment of respite, where hope is more of a placebo than possibility. What I mean is a thoughtful response that looks at the with the violence and the cynicism of today in the eye, and through this imagines a tomorrow that is flawed yet better, a world that is fraught yet bolder. In some ways, ‘Everything for everyone: an oral history of the New York Commune’ by M.E. O Brien and Eman Abdelhadi takes on this tall ask.

When I came across the book, I was skeptical if this would be in the ‘paper with a parable pasted’ genre as both the authors have a research and academic background. Many books written by academics or ideologues who have something to teach or preach use narrative as a wrapper. Whereas, in fiction, if the story isn’t the focus, it could get boring. Take RF Kuang’s Babel where listing the sins of colonialism takes over the story, and you wonder what kind of a book it would have been if it had an appendix, or even two.

Coming back to Everything for Everyone. The academics manage to avoid the preach and perish pitfall by choosing to narrate the story as an oral history. Every chapter is a transcript of an interview, and in choosing this approach, the authors achieve a few narrative wins. As every interview is of a different person, they give voice to multiple points of view, without getting bogged down in figuring out how these stories are related. For, if it had been structured as a story of how the New York commune came to be, then there would have to be more cohesion and threading through of these different narratives, which the each chapter as one interview sidesteps. Second, the interview format allows a person to describe things like working conditions, battles, and commune structure without a ‘show don’t tell’ mandate. For example, if you had to show and not tell someone about how a commune is structured, you would perhaps have a scene where a commune meeting decides on what needs to be done when there is an instance of domestic violence in the commune. Here, one interviewee says, my caregiver hit me and the commune decided on how to address it and provide support to both me and my caregiver. The format of an interview also lets the authors have a dialogue between the present and the future. The authors are the interviewers, and they give voice to the now, people like us who inhabit today. The people being interviewed have witnessed what has changed. Such a framing allows the authors to contrast what they know, the present, with the future presented, and lets us, the readers, find our way into this altered new world.

And it is a new world that is fraught, yet, bold. Everything has changed — ideas about families, communities, gender, nations, and the environment. The first interview is with a Miss Kelley on the insurrection of Hunts Point. She describes how she used to be a sex worker, and how there was severe repression, following which there were riots, and people took over the city and created communes. She speaks about how the communes were formed, the meetings, and the new ways in which people managed themselves and everything else. When asked what the commune means to them, they say, “It means we take care of each other. It means everything for everyone. It means we communized the shit out of this place. It means we took something that was property and made it life.” Sex work has changed to skincraft, and now, Miss Kelley is a ‘skinner’, and in their words, they run a social center in Bronx where ‘ we talk mostly about sex, about work in skincraft, thinking about sex as care.’ The reimagining of sex work as skincraft, a therapeutic practice that touches (literally) on all aspects of life is potent.

“At first, we thought of it like physical therapy for disabled people. Like if we knew someone couldn’t get a good fuck because of how their body looked, a girl would volunteer to work with them. But what people found to be sexy has changed a lot over the years. Now disability isn’t the big deal for sex that it used to be. For a while, we focused on putting on sex parties that were fun and safe and could help people open up to try things they hadn’t. We had some really great ones, and lots of people in the network still organize stuff like that. A lot of girls got trained as therapists, helping people talk through sex. We found sex is really at the center of so, so much. So many emotional problems get tied up with how people relate to sex. Sometimes talking helps sort through all that, sometimes fucking. I have always said the most important thing about a person is what makes them come. A lot of people who got into mental health in the communes kept forgetting that, so we had to be there to keep bringing it up. Some skinners focus on working with people after major changes in their lives, like when they change genders, or go through menopause, or get in an accident that changes how they fuck.”

With every interview, the authors communicate what a new world would look like, where people have taken over, and communities manage themselves. One of the interviews where the person speaks of organising dance parties that became the space for the tech for the insurrection is fascinating as it combines pleasure with politics in a subtle way. The whole future described in the book is an anarchist imagining (before you raise your brows at that, as K, my anarchist friend once corrected me, order is in the very symbol of anarchism, the o twining through the a). Though some of the chapters feel a bit dry and descriptive; one of the drawbacks of the interview format is that it does not allow much for dramatic elements to fuel the narrative; it does not intrude overmuch. There is much in the book to make you pause and wonder, and think, maybe, maybe, just maybe, a changed world is possible. And that to me is a remarkable achievement.