A note to self, a reminder to sway

This was written a few years ago. And somehow thought of it today, as a note to self. A reminder. Yes, all that’s in the title.

—

P. and I studied together. Literally. We spent time in each other’s homes, poring over books, discussing mathematics and electronic circuits. I am sure there was an underlying thread of competition; it used to spurt out in seemingly mild empirical observations such as, “Yeh bhi padh liya?” It was never overt though, almost like some lemon spritzed in tea, just made the relationship a bit tart but never defined the flavour.

P. was diligent and systematic, her notes on mechanical engineering were the map for many lost souls to find that magical pass mark. She studied hard, saved money, and had a booming laugh that often shook her entire fragile frame. That’s why her outburst over a trek seemed so out of character.

Take the last train to Karjat, chug out of Mumbai, and for the price of that train ticket and some extra change, you could make postcard memories. The Western Ghats were meant for treks – be it monsoon or any other weather, you could walk, crib about walking, trudge, dip your hot toes in a cold stream and sneak glances at the new guy who took off his shirt, pick up a gnarly stick, name it ‘Apple Brandy’ and swear you will never part ways. I could tell you many stories, but we are talking about a particular trek.

P. wanted to go for a trek and her folks said no. There didn’t seem a coherent reason – a mix of the unknown and undesirable. P. argued and argued more (with all of us independently egging her over the landline). When she met me, her curly hair scorched as she shouted that if she studied more no one objected; if she decided to work some more (did I mention, she taught tuitions on the side), no one objected; but a trek meant a complete no-no. Even though it was probably the most sanitised form of having fun – exercise, outdoors, and inexpensive, it could not make it into the to-do list.

P.’s folks and my folks, and all the other folks I knew frowned upon fun. I think it has something to do with language. Timepass, mazaa or masti has an illicit texture to it. Especially, girls and mazaa do not mix. Moreover, if there are girls and boys and mazaa in the equation, then the sweat in the trek must have an illicit sheen.

P.’s folks agreed eventually. It was a minor campaign of sorts and it was victorious, but P.’s rant keeps coming back to me at different times. For I realised, over the years, I had bought into what P.’s folks and my folk thought – I was becoming them. Over the years, I have sensed that the commitment to work hard, being diligent, and paying attention to detail have become gospel. Work isn’t an ethic but an ecumenical code that people from different dispositions I know congregate under.

Don’t get me wrong – I am talking about people for whom work isn’t a ‘bad’ thing. Most people I know enjoy their work (I do too). They are those who argue that not having a partner or children is not a sacrifice because a sacrifice implies giving up something important. Vacations do not make sense because there is nothing to escape from. At the same time, I have also heard them murmur that they sometimes miss something – I have a feeling it is mazaa.

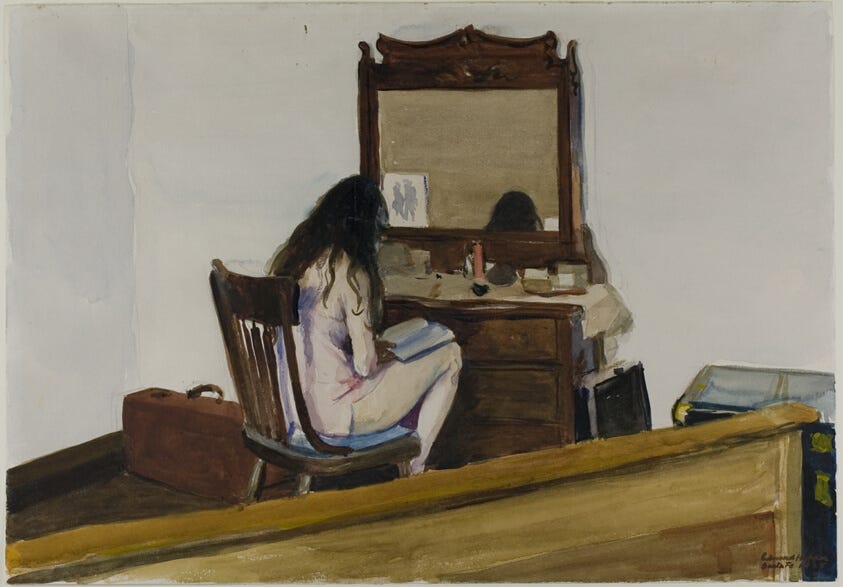

Edward Hopper - Interior (https://www.artic.edu/artworks/14752/interior)

Timepass karna is frowned upon. I remember slouching with the remote control, watching TV, engrossed in some movie or the other, and this whiff of disapproval would float from my mother. It would be nothing too obvious, a tightening of the skin around the mouth, lips slightly thinned, and this extended sigh that would corrode the tube’s empty chatter. Not that the disapproval had any visible effect – I would continue to watch. Yet, there is a niggling thought – maybe it does coat the pleasure, like a spoon dipped in oil used to stir chai.

Somehow, if I have the same mazaa reading a book, which I often do, the disapproval is muted, a notch. (It never quite goes away – book-u, book-u, eppo paaru book-u.) I find pleasure in words, in language. Somewhere, that is seen as a more cerebral pleasure, not related to nerve endings in more touchable places. I think there is something to (the completely useless) theory that the level of disapproval is linked to the level of body involved in taking mazaa. When I slouch on the couch in front of the television, my body is askew. My legs curl, the nightie rides up my legs to my thighs, and somewhere I am unaware of all of that. Maybe if I was dressed in a salwar kameez, my knees tucked in, my limbs cloaked, the disapproval may be toned down a notch. Maybe watching some people on the screen has a more corporeal connect than reading words. Mazaa is thicker and more prurient when it is connected to the body.

Of course, there is food, and here I will tell you about N., who loves rice. N. raises her hand, her fingers slightly curled, her thumb just touching the other fingers, just because there’s that invisible cooked sticky grains in between, when she reminisces about rice while going mmmmm. She grew up in Hyderabad, and she speaks fondly of rice with ghee and anything kaaram. She spoke of rice to a woman who called a domestic violence helpline N. volunteered for, but that is her story to tell.

N., I, and another friend used to go to any Andhra restaurant and have full meals, which translates to hot rice, ghee, anything kaaram, and papad. We would stuff ourselves, till the nadas stretched over our sated tummies, and would waddle back, and fall on the bed. Gifts involved pickle bottles to be consumed paired with rice. Once when she was abed with a version of chikungunya, she told me she wanted to eat something spicy. I trekked to get her this hot garlic fried rice from a Chinese place, and while eating it, me on a chair, and she one the bed, both of us wondered if this constituted as convalescent food. We quickly changed the subject.

I never thought of my body linked to pleasure for a long, long time. Bodily pleasures were hidden, unspoken, and mostly unheard. It was always cloaked, behind doors, under sheets, muffled sounds. Pleasure is one of the words the English language has for mazaa. I just highlighted pleasure and clicked on synonyms and quickly it moved on to ‘gratification, indulgence, and hedonism’. Somewhere, the English language itself is puritanical – pleasure is so strongly associated with sin.

That is where religion needs to take a course in cognitive linguistics. George Lakoff, a cognitive linguist, has a theory of frames. Say you give someone a medicine and ask them not to think of a monkey while drinking it, chances are, they definitely will. By asking them not to think of a monkey, you have setup a frame, a set of associated ideas and metaphors, that involves monkeys, albeit a negative frame. And so, anyone who operates within that framing will draw upon the associated imagery. Sin and pleasure stem from the same frame, something I rediscovered recently when I was at a church service for a funeral.

The priest spoke of sin. As he extolled the virtues of the virtuous, I could not help have naughty thoughts involving a lot of skin, sweat, and other secretions. The more he spoke of heaven, attaining joy, and passage to the yonder, they all metaphorically seemed to map to the embodied pleasure principle.

Legitimate public expression of masti is usually associated with some event and if you are not religious, or do not live with a ‘family’ (read spouse, children, parents), then these days become just marks on a calendar, without any significance. A. whose house now has over 14 dogs had to attend a wedding and when we spoke of it, it seemed like we were discussing a chore.

Recently though, I saw someone speak of pleasure in public. After she had made love, she asked her lover to rub her breasts, soothe them, and dress her, so that the lovemaking could begin all over again. She arched, her hands stretched, and offered all that post-coital languor in one graceful gesture. A base note of musk wafted in the auditorium. It was a solo dance performance on a poem by a poet from the 12th century -- ‘Kuru yadunandana’ a poem by Jayadeva from his work Ashtapadi.

For a while now, I have been seeking this elusive masti in my own life. And finally, it was my friend L. who taught me a completely different definition of pleasure, and she did so just by being herself.

L. lingers.

She lingers over a cup of coffee. When she cooks, her gestures are unhurried, and it is as though the ladle and the pot seem to somehow grow out of her hands. In the evening, after work, she switches on one or two lamps, depending on the day, and they paint shadows and moods. Seeing that, I understood light could fill space without cluttering it. She would chat, maybe with a drink, and linger. She would caress a wooden table revelling in its grain, and then rub it with linseed oil. She would potter around antique shops, just lingering.

She taught me that my mazaa need not be an act separate from the rest of my routine and life. Being mast is not an event. It is not a grand celebration meant for public performance and consumption, but many moments in a day when you become your own refuge and haven. It is intimate and personal and you can sway into it breathing in the fumes of ginger brewing in chai.

Late December, I had gone for a day trip with A to Pondicherry. She had to work, and I just tagged along. At night, we took a walk by the seaside. As we walked on the road, she made friends with many dogs. I was supposed to open the packets of Parle-G and ration out biscuits. We saw a family sitting on a bench, packing up what smelled like a biriyani dinner into steel dabbas. There was a crowd assembled to see a man rise and shine with some divine light coming out of his forehead. The breeze teased us and we wanted to eat something sweet but could not find any place. In the morning, not wanting to leave, I snuggled into A., and she said I was like her dog Rowdy, who liked cuddles. I said Masti, L.'s dog, liked cuddles too. She would nudge me with a paw until I let her settle on my lap and started cuddling her.

As the new year eve darkened, it so happened that Masti was on my lap. It was that moment, when the light seemed to sigh away, saturating all the leaves with that deep shade, and the fairy lights were switched on. I told Masti - I want to sway. That was my wish for the new year - to just sway.

As the quiet breeze sifts through curtains so sheer that they could dissolve in the moonlight, I want to sway. Air would cook slowly inside, and as I let it out, it would shimmer and of course, sway. A step forward, two sideways, a tiny jig, a jump, a pause to catch that breath thrown far away.

Sway.